TLDR: In this post I discuss using a national popular vote weighted by the electoral college to elect the president. This approach would empower voters by expanding political influence outside of ‘battleground states.’ It would also preserve the existing biases built into the American electoral college (thereby making such a system legislatively palatable across party affiliations and electoral college traditionalists)1.

Irrespective of political party or disposition towards direct democracy, the winner-take-all approach applied by most US states to allocate their electoral votes for presidential elections has clear drawbacks. These include:

- incentivizes only campaigning in battleground states

- less reliable outcomes compared to alternatives2

- incentivizes policies that benefit battleground states over the interests of ‘all Americans’

- promotes a feeling among much of the electorate that their vote is unlikely to influence the election

In the last several years3, the movement for a national popular vote to elect the president has gained traction. A compact between states to vote for the national popular vote winner has been passed in states representing 196 of the 270 electoral votes required for the agreement to have legal force4.

However partisanship makes transitioning to a national popular vote difficult. For any given presidential election cycle, the electoral college may favor a particular political party5. Hence it may be against the advantaged party’s interests to support a change to the election process (likewise, the disadvantaged party has an incentive to support a change in the election process6). Therefore a cynic could argue that getting the requisite number of states to legislate support for the national popular vote compact is almost synonymous with winning the election. Even a national popular vote that was passed into law may be politically fragile, and at risk of frequent challenges depending on the state-level political party in power.

The goal of the National Popular Vote initiative is to make every vote matter equally. However if we weaken this goal to be: make the importance of votes more equal than they currently are7, it may be easier to change the electoral system in a way that is less likely to agitate partisans or traditionalists attached to the unequal allotment of influence inherent in the electoral college.

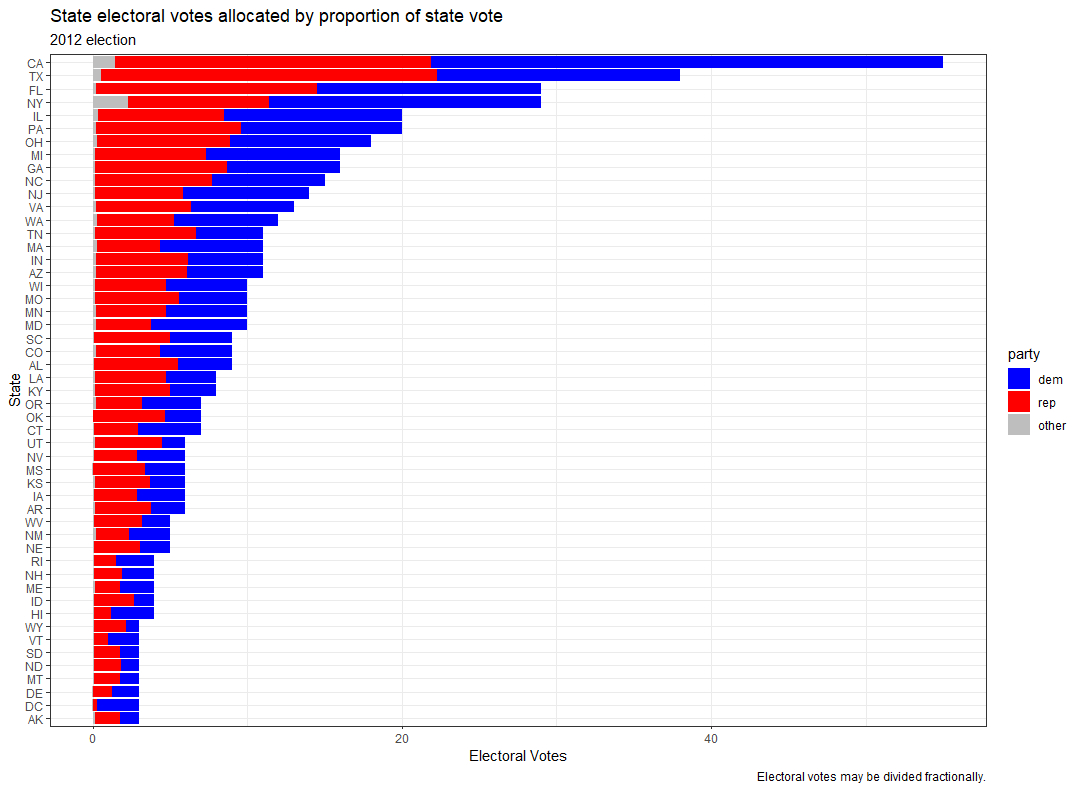

I propose that a popular vote weighted by the electoral college deserves consideration. Such an approach is equivalent to having the allocation of electoral votes in each state be based on the popular vote within that state. For example, if a state has 30 electoral votes, and 55% of those go to the Republican and 45% to the Democrat, the Republican would receive 16.5 votes and the Democrat 13.5. Let’s apply this across states for the 2012 election.

Aggregating these for the 2012 election, the Democrat (Obama) would have received 271.4 electoral votes, the Republican (Romney) 255 electoral votes, and other candidates 11.6 electoral votes. This represents 50.4%, 47.4%, and 2.2% respectively. Describing outcomes in terms of ‘proportional allocation of electoral votes by state’ or as a ‘popular vote weighted by the electoral college’ are interchangeable8. However percentages are easier to articulate, hence I will use the latters terminology for the remainder of the post.

A national popular vote weighted by the electoral college would truly empower small states9 whose voters’ ballots could be worth as much as three times those of larger states10.

State Population per electoral vote from the 2010 census, Wikipedia, National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

While this may seem horribly unfair, it only makes the existing biases built into the electoral college more transparent. Also11, it still represents a major improvement in representativeness over the existing system – where only a ~quarter of the population’s votes make any substantitive difference in the outcome of the election (those votes in battleground states12).

A weighted national popular vote would likely preserve (at least in part) any advantage a party has in the electoral college (for a given election cycle). This would make associated legislation potentially easier to pass and more enduring across changes in state party leadership (compared to legislation for a raw popular vote). The weighted popular vote also maintains the essence of the existing electoral college13 – it just replaces ‘winner-take-all’ with ‘proportional’ allocation of a state’s electoral votes (perhaps a less glaring difference compared to adopting a raw national popular vote).

Let’s review what the results would have been in recent elections if applying a national popular vote weighted by the electoral college.

Proportion of electoral college weighted national popular vote won on elections from 1976 to 2016:

| year | dem | rep | other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | 0.499 | 0.476 | 0.024 |

| 1980 | 0.411 | 0.504 | 0.085 |

| 1984 | 0.401 | 0.588 | 0.011 |

| 1988 | 0.454 | 0.533 | 0.013 |

| 1992 | 0.427 | 0.373 | 0.200 |

| 1996 | 0.488 | 0.407 | 0.105 |

| 2000 | 0.478 | 0.480 | 0.042 |

| 2004 | 0.478 | 0.509 | 0.013 |

| 2008 | 0.525 | 0.456 | 0.019 |

| 2012 | 0.504 | 0.474 | 0.022 |

| 2016 | 0.474 | 0.462 | 0.064 |

Since 1976 there have been two elections where the popular vote and the electoral college did not agree (2000 and 2016). The weighted national popular vote would have disagreed with the raw national popular vote once (in the 2000 election) and with the winner-take-all based electoral college once (in 2016)14.

See github repo brshallo/weighted-national-popular-vote for details on data sources and scripts used to produce the above figures and calculations.

How to get it passed?

The beginning of the video “Myths About Constitutionality” explains how we got our current ‘winner-take-all’ systems across states.

Essentially it was a collective action problem whereby states (controlled by one party or another) adopted a ‘winner-take-all’ approach as a means of attempting to maximize their individual influence and give the most advantage they could to their preferred candidate. Once a few states adopted the ‘winner-take-all’ system it created a domino effect whereby all states adopted it15.

Ways of getting around this collective action problem:

- The approach the National Popular Vote initiative has used is to have individual states pass laws that only go into effect once the requisite threshold of electoral votes is reached – thereby not forcing any individual state to ‘give-up’ some of their influence prematurely. The same approach could be taken to push adoption of a weighted national popular vote16.

- Other approaches may be more piecemeal. For example states of similar size and counterbalanced political leanings could agree to pass proportional voting laws simultaneously – thereby not reducing the support to their preferred presidential candidate17. Such an approach would be more effective if fractional votes among electors are allowed18 19. However there is an argument that states would not have an incentive to pass this type of legislation on a piecemeal basis because it would transfer influence to the existing ‘winner-take-all’ states20.

- A US constitutional amendment…

Closing note

In comparison to our current system, the biggest advantage of a national popular vote for presidential elections is not that it achieves perfect representation but that it provides improved incentives for presidential candidates. For example it would incentivize campaigns to give attention to a broader subset of the American public and increase the reliability of election results. However a national popular vote inevitably faces partisan challenges and may give-off the appearance of being too momentous a departure from the norms of the existing electoral college. As a compromise between these systems, a national popular vote that is weighted by the electoral college avoids many of the challenges to legislating a pure national popular vote while still achieving its most important objectives.

Appendix

What about Nebraska and Maine?

In all but two states, electoral votes are ‘winner-take-all’. The candidate winning the popular vote normally receives all of that state’s votes. Maine and Nebraska have taken a different approach. Using the ‘congressional district method’, these states allocate two electoral votes to the state popular vote winner, and then one electoral vote to the popular vote winner in each Congressional district (2 in Maine, 3 in Nebraska). This creates multiple popular vote contests in these states, which could lead to a split electoral vote.

There may be some philosophical appeal to this method for allocating votes however there are still relatively similar problems with it to the ‘winner-take-all’ method when applied to the state. For example,

- if your vote is not in a ‘battleground district’ your vote, once again, may not matter as much (i.e. a ‘battleground state’ is simply replaced by a ‘battleground district’)

- opens-up presidential election to risks associated with gerrymandering

- if this were applied nationally, appealing to specific states could be supplanted by appealing to specific types of congressional districts, e.g. districts with more urban or rural areas (which may influence president’s against ‘looking out for all Americans’)

This post presents potential merits of a weighted national popular vote however it does not represent a personal endorsement.↩︎

A few thousand votes have a greater chance of swaying entire elections in our current system compared to the likelihood of this occurring with, for example, a national popular vote (Heilman, 2020).↩︎

particularly since the 2016 election↩︎

The website of the organization promoting the National Popular Vote initiative outlines the disadvantages of the winner-take-all approach used by most states and provides arguments for employing a national popular vote. The site also provides evidence for the constitutionality of a national popular vote and counters ‘myths’ that a popular vote would overly advantage or disadvantage certain states.↩︎

However the political party the electoral college advantages frequently changes between election cycles (Silver, 2016).↩︎

It’s not a coincidence that the popular vote initiative is gained substantial support from many Democrats following the 2016 election.↩︎

by spreading political influence away from the dozen or so battleground states↩︎

As long as you allow for fractional electoral votes.↩︎

A common refrain for keeping the current system is that it gives small states more representation. However in practice it only empowers battleground states (at least for presidential elections).↩︎

For an alternative approach to weighting influence, see Durran, 2017 which reviews states have the highest or lowest weighted votes based on actual voters (rather than the census). In the article they point-out that many of the votes in mid-sized states actually have the lowest weights. They attribute this to higher voter turnout and note (at the end of the article) that this may be contributed to by many of these being in battleground states.

I did a similar analysis weighting by: \[\frac{totalVotes/nationalElectoralVotes(538)}{stateVotes/stateElectoralVotes}\] Below is a figure of weights for the 2012 election:

regardless of your opinion on the electoral college and whether voters in small states should be afforded outsized representation compared to their population↩︎

“Influence” here is evidenced by campaign events and ad spending among candidates as described by the the National Popular Vote Initiative.↩︎

I.e. it still spreads out votes by states and not just across the population↩︎

In 2016 Clinton would have had a ~1 percentage point advantage over Trump in the weighted popular vote (compared to the ~2 percentage point advantage she had in the raw popular vote). Under the weighted popular vote George W. Bush would still have still won the election in 2000, despite losing the raw popular vote.↩︎

The result of every state adopting it however has, at least in modern elections, resulted in the majority of states’ influence being reduced.↩︎

I.e. the law would only go into effect when states representing 270 electoral votes passed legislation.↩︎

E.g. say a ten vote state that tends to go 60% democratic teams up with another ten vote state that tends to go 60% republican and each pass a proportional voting system simultaneously.↩︎

Interesting article on fractional representatives: http://www.hnn.us/articles/129114.html .↩︎

If such an approach were adopted by all states, it would create the problem of it being more likely that an individual candidates does not receive the constitutionally required 270 electoral votes… which would need to be addressed. Perhaps could be handled by letting voters put a second choice of candidate. Then If a candidate isn’t in the top two, his voters ballots would flow to their 2nd choices (or 3rd, and so-on).↩︎

↩︎“Enactment of the whole number proportional approach on a state-by-state basis would penalize early adopters and quickly become a self-arresting process, because each enactment would increase the influence of the remaining winner-take-all states.” National Popular Vote Iniative